Inspire’s Policy & Campaigns Office, Matthew Coyle, reflects on his recent trip to King’s College London and the knowledge gained at the ESRC Centre for Society and Mental Health’s annual conference.

I had the privilege earlier this month of attending the ESRC Centre for Society and Mental Health’s third annual conference in the august surroundings of the Science Gallery at King’s College London.

Gathering delegates from a range of fields and disciplines – including those with lived experience, academics, local organisers, charity workers and healthcare professionals – the symposium’s focus was on the themes that have emerged from the first five years of the Centre’s interdisciplinary research around rapid social change and mental health.

A packed schedule of lectures and discussions began with a welcome from Centre co-director Professor Craig Morgan, who set out the ways in which the Covid-19 lockdowns of 2020 had affected young people in South London, curbing educational attainment, compounding financial and housing problems, and exacerbating pre-existing health issues.

Professor Jayati Das-Munshi then presented findings on the specific mental health impacts of the pandemic. Even as people living with mental illness were more likely to contract Covid – and die from it – crucial resources were directed into services deemed more vital and acute. She suggested that the absence of parity of esteem between physical and mental health services, often driven by stigma, saw the latter relegated to an ancillary concern throughout the fraught early months of a major public health emergency.

Professor Sally Marlow’s summary of her qualitative study of mutual aid partnerships during that time underlined the influence of dynamic, community-based peer support. While they invariably lacked significant resources, grassroots groups had organised quickly to provide practical and material assistance. They were driven, she said, by a simple motto: solidarity not charity.

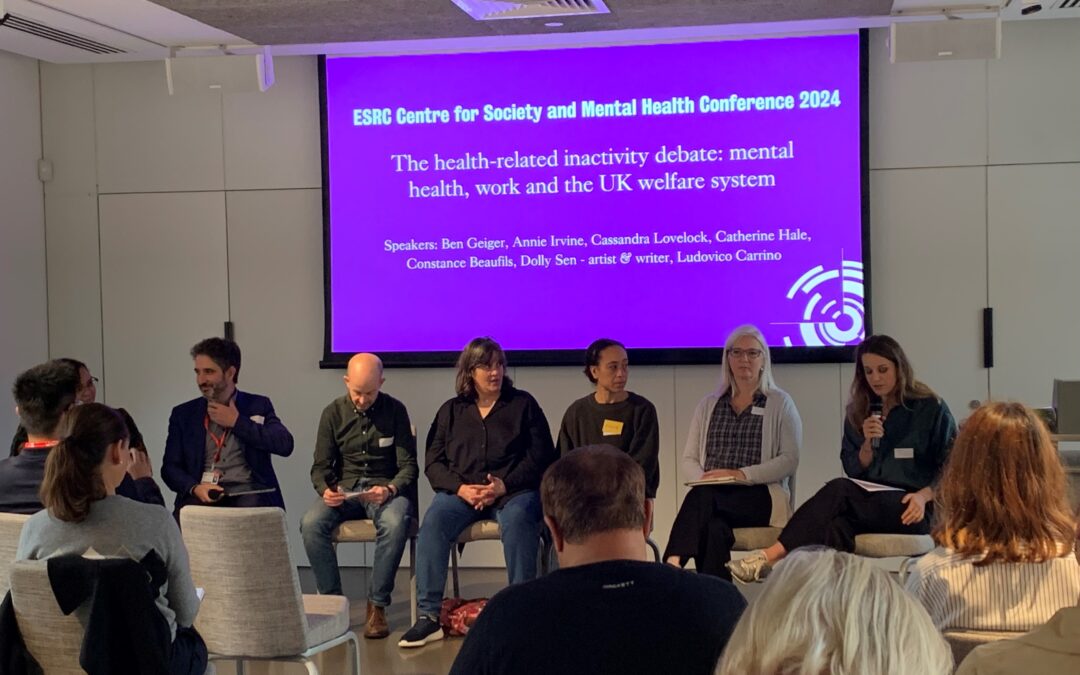

Following a short break, the first panel of the day covered the always topical intersection of health-related inactivity, mental health and social security. Norfolk-based artist and writer Dolly Sen introduced the audience to her latest exhibition, a collection of ‘Fit for Work’ dolls, each depicted in a state of obvious ill health and each representing serious conditions that the Department for Work and Pensions has, in the past, rejected as barriers to employment. “There is no safety net for people in mental distress,” she said.

Professor Ben Geiger explored this topic further, citing the high levels of mental ill health in the social security claimant population. The system, he contended, should presume that all such claimants are experiencing mental illness until it is proved otherwise. According to Annie Irvine, a research fellow at the University of York, conditionality is perpetuating inactivity because benefit recipients are understandably unwilling to step off a narrowly proscribed path for fear of imperilling their existing assistance.

On the subject of workplaces providing flexibility to employees who ask for or require it, activist Catherine Hale confirmed that while pockets of good, responsible practice are visible, there is a stark divide between the accommodations afforded to people within and without the labour force.

After lunch, attendees heard from Sonia Thompson, a member of the Lived Experience Advisory Board, which seeks to ground the Centre’s ethos in the personal experiences of its collaborators. As she continues to work on a paper examining how it fits into a research context, she offered up some fascinating opinions on the role of lived experience. In her estimation, lived experience should not stem from diagnoses or medical models. Instead, it is most useful when individuals have reflected on and contextualised their recovery stories, rendering them capable of passing on something truly valuable: “Lived experience by itself is not enough.”

Echoing this, PhD candidate Laura Fischer stated in her address that “Lived experience is crucial if research and policy are to be meaningful.” And later, Professor Geiger would stress the importance of “models that bring lived experience into contact with the centres of power.”

During the final round of contributions, Dr Rebecca Rhead delved into data relating to self-referral rates for talking therapies in BAME communities and Young Person Champion Jonas Kitisu outlined the serious mental health risks to young Black men posed by disproportionately high stop-and-search rates.

Dr Gabriel Lawson, meanwhile, concentrated on the ways in which public services might better serve people with mental ill health. He described the methods used by the Policy Institute at King’s to “bridge the gap between research, policy and practice”, with ‘policy labs’ – involving multiple stakeholders convened to tackle specific challenges – a key tenet of this work, and pointed out that public services have a “broader social purpose” than a remit confined to educating children, tackling waiting lists and growing the economy.

The insights coming out of the conference were fascinating. They demonstrated the real links between research and service delivery, while also highlighting the extent to which we at Inspire, via our SURF initiative, are already leading the way in the fields of lived experience and service user engagement. As providers everywhere continue to do the best for the people they support, it’s heartening to learn from others on the same journey.